What You’re Getting Wrong About Anne Boleyn: Rumors, Myths, & The Truth

What kind of woman comes to mind when you think about Anne Boleyn? For most people, likely a sexy, scheming “other woman.” Homewrecker? Whore? Mistress?

Maybe you think of Anne as someone who overthrew Katherine of Aragon without a thought. Someone who was experienced sexually, who used her allure and wit to trick the king into marrying her and leaving Katherine: a David lusting after Bathsheba, a temptress.

The truth is, while we have a lot of facts about Anne, Henry, and their relationship, there’s far more we don’t know. In a time when court intrigue was everything, when survival was quite literally a game of thrones, a question of who had favor, who was on top, who was in the king’s ear, it’s hard to determine emotions and motivations from documented evidence. We can read letters, but we don’t know what was said out of deep sincerity versus obligation and convention. We can review a list of events and actions, but we’ll never know the driving forces behind some of them. We’ll never know what was really taking place in the mind of Anne Boleyn, or Henry, for that matter.

What we can do is review the facts and make educated guesses, but they’re guesses all the same. Nevertheless, the story of Anne Boleyn as temptress, seductress, scheming whore, has persisted through time, and if you aren’t someone who regularly hangs out in this time period, that’s likely what you know of her: she seduced the king, she lost her head.

She definitely lost her head. But was she a whore? What did she look like? Was she a witch? Guilty of incest? Murder, even?

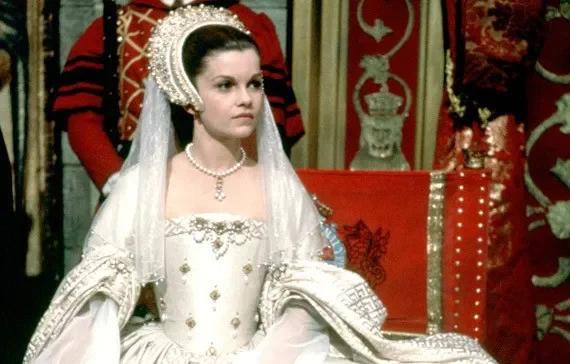

The depictions of Anne range from the sexy-as-hell Natalie Dormer whispering sweet seductions in corridors, to the evil Natalie Portman hellbent on destroying her sister, to the saucy Geneviève Bujold who tries everything in her power to hold out against the desires of a king, to the cold and calculated Claire Foy who wants what she wants and doesn’t care how she gets it. Which one was she? One of these? Somewhere in between?

In my mind, Anne Boleyn looked most like and held herself like Claire Foy. She was absolutely as sexy as Natalie Dormer. I think maybe she did hold out like Geneviève Bujold not to toy with the king, but rather in hopes he would lose interest and leave her be. (I think she had absolutely nothing in common with Natalie Portman’s depiction—no shade to Natalie Portman—this was a scripting problem.)

So what do we know? What’s a myth? What are rumors? What’s the truth? Here are some of the most common ideas I too once held that my research and reading have set me straight on.

Myth: We know what Anne Boleyn looked like.

The Truth: There are no surviving contemporary portraits or physical descriptions of Anne.

Where it comes from: It’s easy to assume the portraits crediting the sitter as “Anne Boleyn” are in fact, Anne Boleyn. But it’s a little more complicated than that since none are both undebated as Anne and contemporary.

Nicholas Sander’s description of Anne has long survived:

“Anne Boleyn was rather tall of stature, with black hair, and an oval face of sallow complexion, as if troubled with jaundice. She had a projecting tooth under the upper lip, and on her right hand six fingers. There was a large wen under her chin, and therefore to hide its ugliness she wore a high dress covering her throat.”[i]

My previous conceptions: While I understood Sander’s description to be propaganda, I didn’t know that there is no contemporary likeless of Anne and believed the Hever Rose and NPG portraits to be accurate and undisputed representations of her.

Questions to consider: How accurate is a painting completed years after someone’s death, in a time where people sat for portraits? Whose memory is being relied upon for physical descriptions of Anne, whether artistically or verbally?

What the research says: Nicolas Sander was born in 1527, and Anne died in 1536, meaning even if he did meet her in person (unlikely), he was nine years old. As Helene Harrison points out in The Many Faces of Anne Boleyn, Sander’s goal was to reflect negatively on Elizabeth I by emphasizing the tainted reputation of her mother. Deformities, during this time, were seen as punishments or reflections of sin, and so while Sander is often partially credited with perpetuating the rumor Anne was a witch, Harrison argues rather than promoting Anne as a witch, his purpose was to paint her as a heretic. [ii] If Anne’s outward appearance reflects her inner appearance, accusations of adultery and incest seem more likely (and if Elizabeth I was born of such a woman, what does that then say of her?) Because his goals are based in propaganda, we can’t trust him as a source.

George Wyatt, grandson of Anne’s supposed lover Thomas Wyatt, responds to Sander’s descriptions of Anne in his work Life of Queen Anne Boleigne, calling her a [she was] a rare and admirable beauty,” though acknowledging she was not as white as was preferred at the time and did have several small moles.[iii]

There are many images that are said to be of Anne, including the Hever Castle portrait, the National Portrait Gallery portrait, the Chequers ring, and two sketches by Hans Holbein. (For more on the various supposed Anne images, check out Adam Pennington’s post here.) There is debate on all of these images, with the only confirmed accepted image being a badly damaged coin in short circulation in 1534. Owen Emmerson has recently suggested the NPG portrait, considered by many to be an accurate representation, though not contemporary, may have been painted from a template of Elizabeth I.[iv]

While many historians seem to agree there are some consistencies (dark hair, olive/not super pale skin, piercing eyes), there’s not enough description wise in contemporary accounts for us to confidently link any of these portraits to Anne—and what’s more, they all look like different women!

Rumor: Anne Boleyn had six fingers. (“You have six fingers on your right hand. Someone was looking for you.”)

The Truth: She had five fingers (ten in total—see video clip below!)

Questions to consider: Would someone with that kind of deformity have served three queens and be crowned queen herself? If this was true, why are there no contemporary reports to corroborate this?

Where does this come from? In his work Rise and Growth of the Anglian Schism, Nicholas Sander reports that Anne had six fingers. This is the first recorded instance of this rumor, which has persisted in pop culture.

Steel Magnolias is one of my favorite films of all time, and I can’t think of the six-finger rumor without thinking of this scene:

My previous conceptions: Y’all, when I tell you how betrayed I feel—the first time I heard Anne Boleyn had six fingers was from a Beefeater at the Tower of London. I distinctly remember standing St Peter ad Vincula with a group of my classmates, being told by a Yeoman of the guard that Anne Boleyn had six fingers and this was confirmed by the examination of her remain. I swear he told us that’s how they identified which remains belonged to Anne—because hers had six fingers. A mis-memory? A Beefeater fucking with some college kids? A tour guide who knew this was a fun, memorable story for a group of tourists? No idea.

What the research says:

We’ve already established we can’t trust the reports of Catholic propagandist Nicholas Sander. But The grandson of one of Anne’s supposed lovers (Thomas Wyatt), George Wyatt also mentions a finger deformity. Instead of an extra finger, he claims Anne had one small extra fingernail: “[t]here was found, indeed, upon the side of her nail upon one of her fingers, some little show of a nail, which was yet so small, by the report of those that have seen her…” [v] Susan Bordo points out that even a deformity as small as an extra fingernail could, in this time, be seen as a connection with the devil.[vi] If Anne had a deformity as pronounced as a sixth finger, it’s unlikely she would’ve been selected as a lady in waiting to three queens and then crowned queen herself. It’s even less likely this wouldn’t be mentioned in other contemporary reports, especially by those of her enemies.

In 1876, the Victorians exhumed the bodies buried in St. Peter ad Vincula, and no skeletons were reported to have six fingers. Dr. Fredrerick Mouat was tasked by Queen Victoria to identify the remains. He described in detail the remains he believed to be Anne Boleyn—including her hands and feet.[vii] (You lied to me, Beefeater, you lied!)

Helene Harrison speculates in The Many Faces of Anne Boleyn that the reason Anne’s fingers are shown so prominently in the Hever Rose portrait is precisely to negate those rumors. The portrait clearly presents a woman with no extra fingers or fingernails.

Hever Rose portrait, Hever Castle

Rumor: Anne became sexually experienced while at the French court.

The Truth: It’s very unlikely sleeping around at court would go unnoticed, and even less likely Anne would remain in employment after it was discovered. It’s even less likely there wouldn’t be contemporary reports of this.

Where it comes from: Reports from Eustace Chapuys, perpetuated in film adaptions.

Questions to consider: Are the writers of these letters/reports reliable? Could they have received incorrect information or be giving incorrect information? Can we fact check any of this? What hard proof/evidence is there to corroborate this?

My previous conceptions: This seemed plausible to me, given the rumors about Anne and Mary, my lack of understanding of foreign courts and ladies in waiting criteria, and the source materials.

What the research says: In her book The Creation of Anne Boleyn, Susan Bordo breaks down the issue of reliability not only with sources like Chapuys, but even with the way historians relay this information as facts. She highlights phrases that are often used that suggest fact where fact is not present. One passage I love analyzes a line from Alison Weir that reads:

“In 1536, a disillusioned Henry told Chapuys in confidence that his wife had been “corrupted” in France, and that he had only realized this after their marriage.”[viii]

Bordo explains: “It’s easy for the reader to overlook the fact that Weir only ‘knows’ that Henry was ‘disillusioned’ about Anne’s ‘corruption’ because Chapuys says so… Henry told him this ‘in confidence,’ so there’s no way of fact-checking. And even if Chapuys was being truthful, there’s a good possibility that Henry’s information was not trustworthy.”

Furthermore, Bordo points out that if Queen Claude had caught even a whiff of such scandal, she “would have undoubtedly kicked her out of court.” [ix] Mary, after all, doesn’t stay in the French court during the changing of the queens—but Anne does.

In Anne of the Thousand Days, Anne confesses nonchalantly to Thomas Percy she had lovers at the French court from a young age. The seemingly carelessness and shrug that accompanies this confession in this scene feels out of touch with a time in which virginity was a woman’s most valued possession—even if confessing to a betrothed.

Rumor: Anne Boleyn had Katherine of Aragon poisoned.

The Truth: There is no evidence that suggested this, not to mention this would be a difficult endeavor.

Where it comes from: Once again, our guy Eustace Chapuys.

Questions to consider: What advantage would this have held for her? (She’s already married, and by this time, pregnant again.) Who would she have employed to carry out this order, and how would the order/the orchestrator have carried it out unscathed? Who, serving in Katherine’s household, would betray her on behalf of Anne? Is there any concrete evidence to suggest this, or rumors alone?

My previous conceptions: This seemed a far stretch to me the first time I heard it, but then again, how many times had I heard Anne had said she wished to see the Spaniards at the bottom of the sea?

What the research says: Susan Bordo reminds us that “the idea that Anne was plotting to murder both Katherine and Mary was a special obsession of Chapuys.” [x] To support this, she cites a letter from Chapuys to Charles V written in May 1534:

“Nobody doubts here that one of these days some treacherous act will befall [Katherine]… the King’s mistress has been heard to say that she will never rest until he has had her pout out of the way…[xi]

In January 1536, after Katherine has died, Chapuys repeats the notion that Anne schemed to murder Katherine. He also reports that when Katherine’s body was examined, her “intestines [were] perfectly sound and healthy, as if nothing had happened, with the single exception of the heart, which was completely black… my secretary having asked the Queen's physician whether he thought the Queen had died of poison, the latter answered that in his opinion there was no doubt about it, for the bishop [of Llandaff] had been told so under confession, and besides that, had not the secret been revealed, the symptoms, the course, and the fatal end of her illness were a proof of that.” [xii] He insists Anne has sworn her position won’t be stable until both Katherine and Mary are dead, and goes on to detail Anne’s rational on why they should die, the order of deaths, and so on. [xiii]

Historians and medical experts have speculated that Katherine likely died of cancer or a coronary thrombosis. Alison Weir reports that Princess Mary, however, was told by the examining physician that a “ ‘slow and subtle poison’ had been mixed with a draft of Welsh beer that had been given to her mother just prior to her final relapse.”[xiv]

While it’s true Anne had no soft spot for either Katherine or Mary, committing murder on that scale, from that distance, given the divisions in the country, the proximity an ally would have to gain to Katherine… it simply doesn’t seem very plausible based on the mere word of an ambassador who hated her that she successfully murdered Katherine of Aragon from afar.

Rumor: Anne Boleyn was sleeping with her brother, George.

The Truth: Many of Anne’s own contemporaries, even her enemies, thought this to be unlikely .

Questions to consider: Is there any evidence at all that supports this? How would it be possible for this to occur under the scrutiny of the court? Would Thomas Boleyn not have noticed this, and would he let it go unaddressed if he did? Would Mary not have taken notice of this? Also: just why?

Where it comes from: Anne and George were both formally tried for incest. Nicholas Sander, our favorite unreliable narrator, reports that Anne “considered that her sin would be more secret if she sinned with her own brother, George Boleyn, rather than with any other,”[xv] and Phillipa Gregory runs with this idea in The Other Boleyn Girl.

My previous conceptions: Even as a young teen watching and reading The Other Boleyn Girl, it never crossed my mind this was anything but fiction. Yet, when I brought up Anne Boleyn in conversations, this seemed to be a go-to thought for a lot of people.

What the research says: While it’s true Anne and George were both tried and found guilty of incest, this was shocking to a contemporary audience. Even Ambassador Eustace Chapuys, Anne’s absolute last fan, had to note that no evidence whatsoever was produced of this guilt—only that George and Anne had passed many hours together.[xvi]

An accusation of incest in this time would have been just as shocking as we find it today. But by adding George Boleyn to the lineup, Cromwell eliminates what likely would’ve been Anne’s biggest supporter and opposition. Chapuys reports to Charles V that George Boleyn, in his trial, “replied to well that several of those present wagered 10 to 1 he would be acquitted.”[xvii] With rhetoric skills like that, and the influence he already possessed, George would’ve been a problem for Cromwell, left untouched, as he took Anne down. Toss in an incest charge, though, and he eliminates the Boleyn faction in one swoop. Thomas Boleyn continues to faithfully, and quietly, serve the king; Mary disappears; and Elizabeth dies shortly thereafter. Norfolk was never on Anne’s side, so by adding George to the accused, Cromwell cripples the Boleyn family, ensuring they won’t recover from this shame and humiliation—even if no one believed the charges in the first place.

We have Phillipa Gregory to thank for persisting popularity of this rumor. In no other depiction of these events played out on screen or page does any writer (to my knowledge) suggest Anne and George actually had an incestuous relationship. As a fiction writer, I understand considering every “what if,” especially since when writing historical fiction, there are so many gaps to fill. Part of the fun of the intersection between history and fiction is considering those “but what if this” and exploring that path to find a story that hasn’t been told yet. This is one “what if” that was simply better left unturned!

Myth: Anne was accused of witchcraft.

The Truth: There is no accusation of witchcraft in (what survives of) Anne’s trial records.

Questions to consider: Why is the idea of witchcraft associated with her despite it never being a formal accusation? Was this an idea present in contemporary time or one that emerged thereafter?

My previous conceptions: I did absolutely believe she was formally accused of witchcraft.

What the research says: Oh hey, it’s Nicholas Sander again. Helene Harrison acknowledges that while Sander’s account is likely, at least partially, where this suggestion has come from, “he does not actually link Anne Boleyn directly to witchcraft in his work.” She reminds us that while it is very possible some records are missing from Anne’s trial, we do have a lot of surviving materials—and they don’t mention witchcraft as a formal charge. She goes on to point out that “if witchcraft was mentioned, then it was not technically an offence in 1536. The Witchcraft Act was not introduced until 1542. But accusations of witchcraft could result in the dissolution of a marriage, which is possibly where Henry VIII’s mind was going...” [xviii]

Despite the Witchcraft Act not being a formal charge (in the sense of what was punishable by death, at least), three Queens of England had been accused of witchcraft prior to Anne’s execution—so a precedent for this does, nonetheless, exist. Joan of Navarre and Elenor Cobham were accused of using witchcraft to plot the deaths of Henry V and Henry VI respectively, while Jacquetta of Luxembourg and her daughter, Elizabeth Woodville, who would become Queen of England, were both accused of using charms and love magic to enchant their husbands into marrying them. (Gemma Holman explores this in depth in her book Royal Witches: Witchcraft and the Nobility in Fifteenth-Century England.)

Sander’s Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism was published in 1585. In 1563, Scotland, passed their own Witchcraft Act, and by the 1590s, under King James VI, witch trials, hunts, and executions were in full swing. The descriptions of the bodily deformities outlined by Sander, regardless of his intentions, would’ve brought to the contemporary reader’s mind witches’ marks. The idea of witches having outward deformities reflected the evil inside them.

Chapuys reports court gossip following Katherine of Aragon’s death that “[Henry] had said to one of them in great secrecy, and as if in confession, that he had been seduced and forced into this second marriage by means of sortileges and charms, and that, owing to that, he held it as nul.” [xix] This is often cited as evidence Henry believed Anne had seduced him with love charms—though whether he was being literal or it was used as we might say someone “bewitched us” as we fell in love, more as an expression, is impossible to know.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone plays on this idea by placing Anne’s portrait in Hogwarts:

No contemporary evidence, save this piece of reported gossip, points to contemporary belief in Anne’s own life that she was practicing witchcraft or love charms. Though Anne was never formally tried or found guilty of witchcraft, this myth persists in common misconceptions.

Whatever your feelings about Anne—tragic heroine, seductress, somewhere in between—I hope this at least sets the record straight on some of the more prevailing beliefs about her. As a teenager and young adult, I never believed her guilty of the charges against her, but I did believe a lot of what I now know to be rumors and myths nonetheless. The more I chase Anne, the more she evades me. The more I learn about her, the less certain I am of who she was—and that is precisely why she fascinates me and has captivated me for so many years.

This post is part of The PhD Project, a self-guided, post MA post MFA learning endeavor. These posts are not meant to present new arguments or new materials, but rather to summarize my learnings over the course of this project.

References

[i] Nicholas Sander, Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism, London: Burns and Oates, 1877.

[ii] Helene Harrison, The Many Faces of Anne Boleyn,

[iii] George Wyatt, Extracts from the Life of the Virtuous Christian and Renowned Queen Anne Boleigne. Isle of Thanet: Rev. John Lewis, 1817.

[iv] Harry Cockburn, ‘Anne Boleyn Painting is Actually a ‘Different Royal’ claims historian,” The Independent, 2026. https://www.the-independent.com/news/uk/home-news/anne-boleyn-painting-elizabeth-i-national-portrait-gallery-b2899544.html

[v] Wyatt.

[vi] Susan Bordo, The Creation of Anne Boleyn, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2013.

[vii] Adam Pennington, “The exhumation of Anne Boleyn and restoration of the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula.” The Tudor Chest. https://www.thetudorchest.com/post/the-exhumation-of-anne-boleyn-and-restoration-of-the-chapel-of-st-peter-ad-vincula

[viii] Alison Weir, The Lady in the Tower, New York: Ballentine, 2010.

[ix] Bordo.

[x] Bordo.

[xi] Pascual de Gayangos (editor), “Spain: May 1534: 21-31, “Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 5, Part 1: 1534-1535, British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/spain/vol5/no1/pp166-173.

[xii] Pascual de Gayangos (editor), “Spain: January 1536, 21-31,” “Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 5, Part 2, 1536-1538, British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/spain/vol5/no2/pp11-29.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Weir.

[xv] Sander.

[xvi] Pascual de Gayangos (editor), “Spain: May 1536, 16-31,” “Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 5, Part 2, 1536-1538, British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/spain/vol5/no2/pp118-133.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Bordo.

[xix] Pascual de Gayangos (editor), “Spain: January 1536, 21-31,” “Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 5 Part 2, 1536-1538,” British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/spain/vol5/no2/pp11-29.