The Mystery of Lady Margery Barber

Finding My Family: Part 2

My grandfather and his brother researched our family for years, never quite being able to pinpoint where we came into the States and from where. In less than a week, I’d answered this: we came from England by way of either North Carolina or Virginia. Though I need to backtrack and dive deeper into exactly when and through what port we came, what I do know is that John William Barber (8 generations) was born in Anson, North Carolina in 1738, while his father, George Frances Barber (9 generations) was born in Wiltshire, England in 1720. In 1736, George Barber married Elizabeth Jane Moore in Augusta, Virginia, where she was born in 1719. The Barbers seem to have settled in Anson for quite some time before slowing making their way west to Mississippi over the next 200 years.

“Technology is insane,” I told my mother (a Barber by marriage). “I got further in a week than Papa got in 20 years, all because of online records and websites while he was printing out stacks of paper.”

“True,” she mused with a smile, “but your grandfather was also terrible with the technology that did exist back then.”

Not only was I not tied to a computer and stack of binders while researching, I could do it from the car on a mobile app. My partner was driving us back from an event one night when I exclaimed from the passenger seat, “I’ve found it! I knew it! We are descended from a duke and countess!” He laughed, congratulated me, and said, “I’m so happy for you,” in a both sincere and teasing way. I proudly reported to my father and sisters we were descended from Sir John Barber, Duke of Suffolk and Lady Margery Barber, Countess of Suffolk.

But then I cross checked records of the peerage of England. I knew that Charles Brandon was Duke of Suffolk during the time of Henry VIII. My hope? I was somehow related to him, and thereby the Grey sisters and so on. (Charles Brandon seems especially douche-ish, but I admit I’ve always been drawn to him for some reason? Perhaps this was why!) What I found? Absolutely no mention of a Barber, ever, holding any title, let alone that of Duke of Suffolk in the mid-1400s. In fact, it’s pretty clear from the records the de la Pole family holds this title—during the exact time my ancestor is supposed to have held it.

But the real mystery is Lady Margery Barber. There seem to be three different Margery Barbers that pop up on family record sites:

one (allegedly) marries John Barber of Fressingfield

one (allegedly) marries Sir Thomas Venables of Kinderton

one (allegedly) dies as an infant

All of these list her birth and death dates the same, 1410-1480. Many have siblings in common. Each varying instance seems to have just enough in common to assume it’s the same woman, but then, just enough off to cast doubt and require further research. Some records report Margery Barber was born in Fressingfield. In those instances, no parentage or other information can be found. Other records report she was born in Hooten, Cheshire and list her parents as William Stanley VI and Margaret Blance d’Arderne. Some records have these parents listed but no trace of a marriage to John Barber. Some have these parents listed saying she died as an infant. Others still have her marrying both Thomas Venables and John Barber—though it seems, based on dates of birth, marriage, etc, these cannot be the same women.

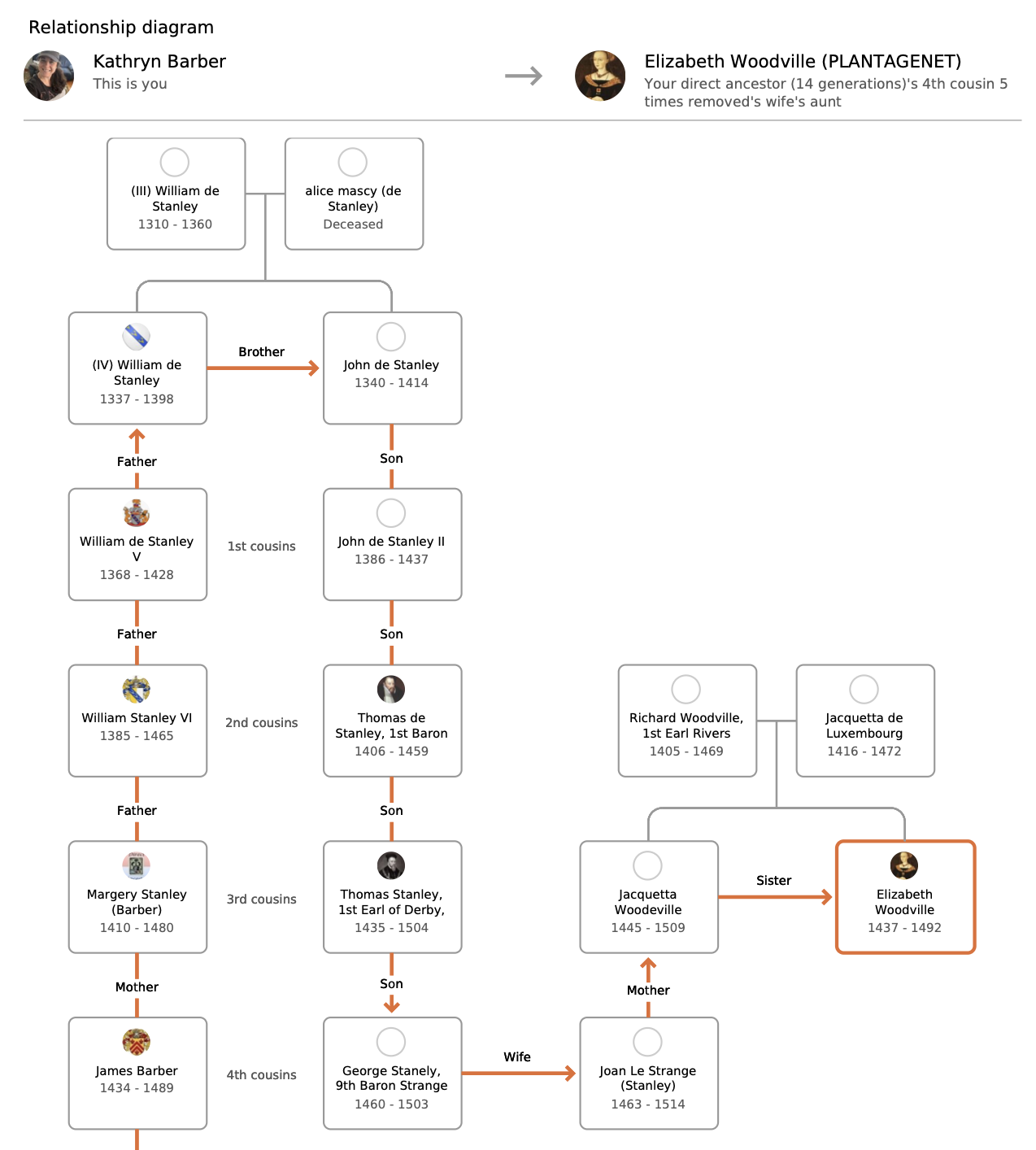

If Margery Barber (nee Stanely), daughter of William Stanley VI is in fact my ancestor (20 generations) by marriage to John Barber, then I am (very distantly) related to Elizabeth Woodeville:

which would mean:

Elizabeth Woodeville is my direct ancestor (14 generations)'s 4th cousin 5 times removed's wife's aunt

Elizabeth of York is my direct ancestor (14 generations)'s 4th cousin 5 times removed wife’s cousin

King Edward VI Plantagenet is my direct ancestor (14 generations)'s 4th cousin 5 times removed's wife's uncle

The Princes in the Tower are my direct ancestor (14 generations)'s 4th cousin 5 times removed's wife's cousins

Henry VIII is my direct ancestor (14 generations)'s 4th cousin 5 times removed's wife's cousin's son

Anne Boleyn is my direct ancestor (14 generations)'s 4th cousin 5 times removed's wife's cousin's son’s wife

and I’d still be right that I’m connected to Charles Brandon, who would be my direct ancestor (14 generations)'s 4th cousin 5 times removed's wife's cousin's son-in-law—just you know, a lot less directly! (Maybe I should explore my other family lines—Delk, Turner, and Renshaw—for closer results?) My gut feeling was that somehow, more closely, the Barbers were tied to the story of the Tudors. And of course, that may be simple wishful thinking after viewing the coat of arms certificate in my grandfather’s things, which listed a John Barber as a clergyman connected to Archbishop Cranmer. (Look, Wikipedia is never a totally reliable resource, but the information it has listed on this figure is interesting.)

Aside: I’ve been researching these folks for months now, trying to connect myself into my favorite Tudor court stories. Last week, in casual conversation, my manager at work tells me he too has been researching his family and he is a direct descendant of Mary Boleyn. (Can you hear me containing my jealousy, Zach?)

The trouble is I can’t find any solid research about the mysterious Lady Margery Barber outside of family tree websites. She’s all over Ancestry, Geni, MyHeritage, and so on, but when it comes to real archives and sources? Poof. Girl is gone. I could explore other family lines and try to find more direct connections to my favorite historical characters (and I will, eventually), but right now, I am beyond intrigued at solving the mystery of Lady Margery Stanley Barber. I want to know:

Who were her parents?

Where was she born?

Is there more than one Margery Stanley? (very possible)

Who did Margery Stanley, William Stanley’s daughter marry, and where?

Here are some of my primary challenges in chasing her down:

Similarity of names: An important consideration is that in early modern England, many people had the same Christian names.

For men, common names include John/James, Richard, Thomas, Edward, Henry, Charles, and Robert. For women, Katherine, Anne, Margaret, Mary, Elizabeth, and Isabel. Moreover, some names that to us are very different would have been interchangeable depending on level of familiarity, spelling variations, nicknames, and so forth. For example, Agnes and Anne would be considered the same name, with Anne being an Anglicized version or Ann/e appearing as a shortened version of Anne. In the film adaptation of Hamnet, Shakespeare’s wife, more commonly known as Anne Hathaway, is called Agnes, pronounced Ayn-yez. Margery was a common shortened version of Margaret, and Isabel an Anglicized version of Isabella. To contemporary audiences, these names would denote different persons, but in early modern England, the names Agnes, Ann/e, and Nan could all refer to one singular person. The addition of the letter n preceding a name beginning with a vowel (Anne, Edward becoming Nan, Ned) would suggest not necessarily a different person, but rather, an affectionate version of the name, abbreviated from “my Anne” or “my Edward,” becoming Nan or Ned.

This is important to consider, as records may show, for example, Margaret Barber and Margery Barber in the same family tree slots. This doesn’t mean there are conflicting reports of wives, but are likely the same person. My mysterious Margery Barber could actually be a Margaret.

Spellings: Just as names commonly shifted in reference to the same person, so might spellings of someone’s Christian or surname.

Barber, Barbour, Barbar, de Barber, and so on, could all refer to the same family. Not only might those referring to this family spell the name differently in fluidity, so might the members of the family themselves. It’s not until William Caxton introduces the printing press in the 15th century that spelling begins to be standardized to maintain consistency in printing. The first dictionary isn’t available until Robert Cawdrey’s in 1604, a movement toward standardized spelling, at least in print. At this time, however, handwritten spellings would still have varied significantly. This is why we see Henry VIII’s queens’ names, with the exception of Jane Seymour, written in various spellings. While Catherine was the more traditional spelling, the K variant was also used in early modern England. Henry VIII’s fifth wife signed her name Kateryn, but we more often see her referred to as Catherine or Katherine. Similarly, Henry VIII’s first and sixth wives are also referred to with interchangeable C and K spellings. Some scholars refer to his fourth wife as Anna of Cleves, as Anne was the Anglicized spelling. Many sources also refer to the Boleyn family with spellings such as Bullen, Bolleyne, and Boullan. In contemporary writings, we would consider, for example, Katherine Barbour and Catherine Barbar to be separate individuals, but in early modern England, these spellings could refer to the same woman. This is essential to remember when evaluating records, as a spelling variant does not necessarily (but could!) denote separate characters.

Meaning, Margery Barber could also be Margaret Barbour, Margery Barbar, Margaret de Barber….

No records: It’s not until 1837 there’s a formalized process for documenting births, marriages, and deaths in England.

Prior to this, records are held by parishes in various counties. In 1538, Thomas Cromwell ordered parishes to keep records of baptisms, marriages, and burials. However, many do not survive, or were never documented properly to begin with. This is why the date of Shakespeare’s exact birth is unknown, for example. As The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust explains: “Shakespeare’s baptism is recorded in the Parish Register at Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon on Wednesday 26 April 1564. Baptisms typically took place within three days of a new arrival, and parents were instructed by the Prayer Book to ensure that their children were baptised no later than the first Sunday after birth. This means that it’s unlikely that Shakespeare was born any earlier than the previous Sunday, 23 April. Given that three days would be a reasonable interval between birth and baptism, 23 April has therefore come to be celebrated as his birthday.” If a parish created a record of a baptism, and if that record still survives, we can guess an approximate birth date based on the recorded baptismal date.

I tried to obtain burial records from the Suffolk Family History Society, but was met with a reply that they hold no records prior to 1538. This is also cause to question some of the birth records recorded on websites like MyHeritage or Ancestry.com, especially when the birth dates prior to 1538 are not recorded even in parishes. It calls into question where these exact, or even circa dates, were obtained, especially since one error by one user can be perpetuated then across multiple family trees.Family Tree Website Errors: While many records prove difficult to verify, records of peerage offices held are easily accessible.

On MyHeritage, I’ve found numerous records referencing “Sir John Barber, Earl of Suffolk.” Many websites, including Ancestry, Genealogie Online, etc, record Sir John Barber, Earl of Suffolk, as being born in Fressingfield in 1410, marrying Margery Stanley in 1434, and dying in 1457 in Fressingfield. However, if John Barber were, in fact, an earl, he would be addressed as Lord, not Sir. Records referencing his wife also vary, with some styling her as Lady Margery and others as Countess. The title of Earl of Suffolk is held by William de la Pole, inherited five years after the supposed birth of John Barber. In 1444, William de la Pole negotiated the marriage of King Henry VI to Margaret of Anjou, earning himself a promotion from earl to marquess, and later on, in 1448, he’s created Duke of Suffolk. Edmund de la Pole, William’s son, succeeds him as Earl of Suffolk after the death of eldest son John in 1491—the demotion from duke to earl being a result of fighting against Henry VII, who took the throne in 1485. If the de la Poles hold the titles of earl, marquess, and duke from 1399 until Henry VIII executes Edmund de la Pole in 1513, when does John Barber (c. 1410-1457) hold the title of Earl of Suffolk? The problem: he can’t.

Eventually, I’ll come back to researching other lines, pinpointing where we came into the States, and more on how we moved from North Carolina/Virginia to Mississippi. Margery Barber aside, I’m still certain we are the Barbers of Fressingfield, and I’ve done some preliminary research on the small town and found some documents referencing Barbers that are showing up in my ancestry line. But for the present moment, I’m still chasing the ghost of Lady Margery Barber (who very possibly was never a true “Lady” at all….).